Datong

On the evening of June 23, 1996, our train pulled out of Beijing and headed west into a lightning storm. After 300km (185 miles) and nine hours of sleep, the crew woke us at 5:00am to a view of rolling hills covered with short, green scrub-grass and orange-clay houses, as well as smokestacks from industrial sites. We were the only Westerners arriving on the train and, along with the rest of the passengers, were practically alone in the Datong (DAH-toong) station at 5:20am; locals staring at us like we just got out of a space-ship -- they were quiet, but pretty beat-up looking. One beggar spotted us in the waiting area: surprising how fast they can move on bad crutches!

Not seeing a place to store luggage, we walked up the street following a friend's directions. Of course, we missed our turn. Taking the second turn we met an older gentleman exercising. He escorted us along a path behind the hotel through an alley, to the front of the hotel. The plaza outside was packed with people of all ages exercising and playing, as it was Sunday, their day of rest, if that makes any sense. The younger ones were playing badminton and a modified game of hackey-sack.

Datong is known for its coal mines, and has a population of more than two million. It couldn't be much uglier, with its concrete, steel, and coal dust. The pollution burned our eyes and throats. Yet somehow, the air was dry and cool, with the sky being a pretty bright-blue, lightly covered with whispy clouds.

This is the kind of place that inspires you to take care of business fast and leave as soon as possible. Dropping our bags in our room, we headed straight back to the train station to find a city bus. CITS (government tourist office) was determined to put us on one of their inflated tour buses. We escaped the fumes from the kerosene-doused wood-chips. Workers were busy pushing them around the the station with a dust mop to clean the floors. We went off on our own since we knew the city had a decent bus system.

Outside the CITS office, we met a Chinese woman who spoke English very well. She tried to convince us how difficult it would be to get to the caves unless we spoke Chinese, or went with someone who did. We confused her by saying that we weren't going to the caves -- isn't everyone visiting Datong here to see the caves? She watched, puzzled as we went on our way.

We hopped on a city bus, and the conductor let us know where to get off to catch another bus out of the city. An eager crowd of minibus touts immediately welcomed us. Showing them the Chinese characters for the Hanging Monastery, they practically lifted us into their bus. We asked the price and were quoted twice the going rate. A woman seated behind us heard the rate and busted out laughing, so we got out and started walking to the next minibus. This got their attention, and they quickly dropped the fare to the standard rate. They made up for their 'loss' by dropping us uphill from the entrance to the monastery when we wouldn't agree to return to town with them -- you can't win with these buzzards!

We expected the highly over-rated monastery to be built into the rock, but it just sat flat on a shelf against the cliff face with poles supporting the overhanging portion. It was rundown, and even less impressive up close. It was a museum, as the monks had long since abandoned it.

After strolling through the monastery, we returned to the parking lot and were summoned by a minibus driver. He asked too much and wouldn't bargain, so we immediately left and started walking back up the hill. We were 50m (165 ft) away when he woke from his gouging stupor and started yelling "Hello" to us. He waved us back and agreed to the normal price. We were back in dingy Datong almost three hours later and wearily returned to our hotel for an instant-noodle dinner.

The next morning, Marc went to the train station to buy tickets. He was sent to an office on the side of the building. There he was given a piece of paper and escorted up a narrow staircase to an office window on a landing between floors. After waiting thirty minutes, the window opened and he received more paper. He was then sent back to the other office to wait in line with others.

After twenty minutes, a man came in and cut in line. Marc stared directly at the guy and repeatedly told him in English to get in line. Nobody understood Marc, but the meaning was clear and the guy went to the end of the line. Marc paid some money, was given a small cardboard ticket and was sent back to his starting point, the main ticket window. He finished paying and received the rest of the ticketing information. He returned to the hotel for the usual post train-station trauma recovery! Sometimes it's better to pay the small charge and let CITS get the tickets.

When we started eight weeks earlier, we tried to determine the right bus from Kunming to Dali. We never realized how valuable learning to recognize Chinese characters would be. It saved us time and money when buying and verifying bus and train tickets, and preventing scams. It's funny how you know you've arrived in a city, since you find that the name of the city is the only thing you can read. It's surprising the number of times they use it on signs and businesses. Reading the train schedule was a real challenge, and helped out a bit, making us more confident of our ability to navigate.

Although the language isn't a mystery, there is a formidable language barrier. Still it is no more difficult than in other countries, if you have a book, learn a few words, or are a good mime. After six weeks, the tones finally became familiar enough for us to pronounce words consistently, and well enough to be understood.

When you stay in a place long enough, the locals get used to you and loosen up. The workers at the construction site near the hotel had no problem remembering us, but saw that we had our packs on and were leaving, so they gave us a farewell "Hello!" The kids also gave us curious "hellos." Our opinion of Datong improved a bit. The CITS guys spotted us again and offered a tour, and to get us train tickets. They were astounded to hear that someone had actually accomplished both on their own.

Locating the baggage locker room outside the station, we locked our bags down inside and were ready to do some more sightseeing. As we went to pay, the team of surly, women baggage clerks quoted a rate three times the original. We could clearly see the correct rate on the other bags and in the logbook entries altough some small bags had lower rates, none came close to what they were trying to gouge us for. We had nearly given up on sightseeing when a visit to CITS confirmed the correct storage rate, and directions to another locker room. Marc checked it out, and returned with good news, yet again by the time we got there with the bags, the rate had tripled. No use arguing, we just walked out.

The greed in transactions is exhausting to deal with, and was nowhere near the fair bargaining we were used to. We know we were overcharged much of the time, but we accepted that going in. Some tourists like to say that the Chinese are always trying to steal from them, yet we didn't have problems like that, nor did we ever catch anyone short-changing us. In fact, they sometimes gave back too much by adding the total wrong or counting the change wrong -- perhaps they should dust off their abacuses. We always gave it back, not out of the principle, but only to see if it shocked them that they had made a mistake, or that somebody actually gave it back. Not surprisingly, they showed no response.

We decided to pay the CITS office another visit and tell them what we thought of this hole-in-the-ground. They surprised us by offering to hold our bags for the standard rate. After eating our way through a stack of eight delicious boazi (steamed buns filled with pork, cabbage, and more), we boarded a minibus to Xin Kaili on the west side of town, then transferred to the #3 bus.

The road wound through brown, desolate, and barren hills dotted with adobe homes. Reaching the mining area we saw huge, coal-laden trucks. In an hour we had gone from spotlessly clean to looking like coal miners covered with black dust. We looked exactly like the sides of the road. The cheerful bus attendant made sure we got off at the Yungang (yoon-gong) Buddhist Caves. The caves are a UN World Cultural Heritage Site that Marc knew about from reading Lynn Salmon's "A Trip Along the Silk Road."

Dodging a Japanese tour group, we visited

twenty-one of the fifty caves dating back to the 5th-century. Only two of the

wooden monasteries were still standing, leaving the other caves exposed to the

elements, and partially eroded from the Gobi Desert winds. It's easy to see why

monks would want to stay in the caves, as they are cool inside and provide a

nice escape from the heat. The colorful frescoes and Buddha statues sculpted

into the side of the sandstone mountain were impressive, some as high as 17m (55

ft), inside 20m-high (64 ft) caves.

elements, and partially eroded from the Gobi Desert winds. It's easy to see why

monks would want to stay in the caves, as they are cool inside and provide a

nice escape from the heat. The colorful frescoes and Buddha statues sculpted

into the side of the sandstone mountain were impressive, some as high as 17m (55

ft), inside 20m-high (64 ft) caves.

After our tour, we crossed the street and stood on a wall, where we were blasted by a coal-dust storm every time a vehicle passed. Finally, we were rescued by the bus twenty-five minutes later. A lady in the back of the bus showed us a box with three baby owls in it -- wonder where they were going!

Back at the intermediate bus stop on the west side of Datong, we were spotted by the driver of a futuristic fiberglass trishaw. He wanted to know where we were going and pointed to his vehicle, while Marc pointed to the bus stop sign. This drew a chuckle from twenty red-cheeked locals (of Mongolian descent) who crowded around to watch the show.

Crowds in China are magnetic, attracting anything that passes, so we were soon surrounded by piercing eyes and attentive ears. A couple next to us struck up a 'conversation' with their limited English, which the crowd enjoyed greatly. They'd been studying English for a year and seemed to be enjoying the practice. Getting on the bus together, they welcomed us to Datong and asked how we liked it -- a trick question of sorts!

Back at the train station, we stopped to get our bags. This time we avoided the kerosene fumes by hanging out in the CITS office and talking to the agent for an hour. He asked what we thought of Chinese toilets -- another trick question! We were used to them, but he'd met many Westerners on tour groups who were appalled. He said he had a Western-style toilet in his home. He also talked about theft and how he has to live simply to avoid being a target, although he could afford better. Houses here are like prisons with steel doors, and window bars. He said he saw a man a few nights earlier stealing a manhole cover, which would be sold to the metal company. Marc told him about the aluminum rails that are stolen along US bridges, and that some people try to steal copper wire from streetlights, only to be accidentally electrocuted to death.

The train rolled in, so it was time to say "Zàijiàn" and find a comfortable spot for the 36-hour, 1600km (1000 mile) ride. (As if Datong didn't have enough problems, we read that a plague of locusts descended a year later and devoured 265,000 acres of crops.)

Xian

We didn't go there, we didn't even get close. We took a detour northwest through the Inner Mongolian Desert, and down along the Yellow River to Lanzhou. So, why are we including it? Because we are always asked, "Did you go?"

Xian (she-ahn, or see-ahn) is the most polluted city in China, and one of the most polluted cities in the world. It also has a reputation for crime, yet neither of these facts deters us since we have experienced plenty of polluted cities in Asia, and crime is a constant we have to deal with back home. The central attraction in Xian is the Terracotta Soldiers archaeological site. We aren't the best at appreciating such things, especially at exorbitant entry fees. We had given up this idea years ago, but soon after entering China we reconsidered it. We had since learned ways of getting in affordably, and were swept along by the rave reviews. By the time we arrived in Beijing, the negative stories had returned us to our original decision.

One man we met was irate after getting inside. He soon realized that the limited view of the exhibit was all he was going to get. He didn't like the fact that he couldn't walk around the worksite, which has to be kept secure since tourists have a bad habit of touching things. At first they tried to rush him through, but he was determined to get his money's worth. He took his time studying the figures for thirty minutes. Like other visitors, he felt, "It was too clean and new, resembling a fabricated tourist attraction."

For being such an important archaeological site, he was surprised at "how slowly they were uncovering the rest, especially given the enormous profit they were making". Later, we read that the government stopped excavating more sites because the statues were deteriorating due to oxidation. The government also felt that displaying more sites would only be redundant to what is already available for viewing.

Not having gone there, we can only offer you his story. We were still confused by the fact that half the tourists like it and half find it extremely disappointing. We tried to rationalize that short-term tourists sped by on their two-week vacations sporting "rose-tinted" glasses, yet there was no consistency in this theory, nor among the jaded backpackers. For more information on this, see the October 1996 issue of National Geographic.

We had hardly settled into our 'new home' on the train, when Marc started talking to Zhao, a young engineer who was a repair technician for ultrasound machines. This medical equipment is popular since it is used to determine if a fetus is a boy or a girl. Many women terminate pregnancy if the fetus isn't male, even though it is illegal to use the equipment for this purpose.

The One-Child Policy was started in the 1970s after the government realized that its food production could not sustain its population at the high growth rate then. They set the legal minimum age for marriage at twenty-two for men, and twenty for women. This is not enforced in much of the country, although it is enforced in the cities. Their goal was one child per family, and where they have been successful in the cities, but the national average still remains at a high 2.25.

One reason for their failure is the strong desire throughout society for a male heir to continue the family name. In some instances, especially overseas, a son will provide for the parents in their old age. Fines for having more children don't begin to compare to the additional income a son will bring. Government entitlements (welfare) are often revoked too. To meet limits, couples are harassed, women are encouraged to undergo sterilization, and pregnant women are urged to have an abortion.

The One-Child Policy isn't popular, but ways around it are. Many don't register their daughters, others visit relatives in the countryside to conceal the birth from local officials. Some girls are given up for adoption, and sadly there are cases of female infanticide.

Zhao was based in Beijing and was travelling on a business trip to Datong and Hohhot. He said he often travelled to Seattle for intensive training, but didn't enjoy it since there was no time for leisure. He sometimes travels to San Jose to visit his grandmother, who wants him to migrate to the US, but he isn't interested. We thought this was unusual since everyone else wanted to go. He likes it here since it is his country, he is comfortable, and he enjoys being in his culture and eating his food.

We had been talking for a while when a vendor strolled by with a cart of food, reminding us that we were hungry. Zhao invited us to join him in the dining car, and we followed him through six cars, passing some large men who didn't look very Chinese, but did say "Hello" and "Hi" to us.

The kitchen staff was sitting around having dinner and told Zhao that he was late. Chastised, we started to leave with dejected looks, when they called us back. Minutes later, the table was loaded with food. There were plates of inedible pork-fat with hot chilis, celery and mushrooms sauteed with strips of steak-fat, scrambled eggs with tomatoes, eggplant with chilis, three bowls of rice, and three bowls of soup. Zhao polished off two bowls of rice and we split one bowl, doing our best to make a dent in the filling meal. He insisted on buying, which is always a pleasant surprise in China.

We sat for a while talking, then started the long trek back to our bunk. Halfway there the BIG guys detained us, while Zhao disappeared off in the distance. The guys turned out to be Greek-looking Kazakhs from Yining, near the Soviet border. They were on their way back from a business trip in Beijing. First, they wanted to know if either of us was Muslim. Then they gave Marc his first lesson in the Uighur (wee-guhr, or oi-guhr) language, and were impressed when he rattled off the numbers. With his beard, Marc looked like a bona fide member of the group.

A well-spoken woman and a Chinese man who wanted to practice a few English words he'd mastered, helped translate from English to Chinese so the Uighurs could teach Marc some Uighur words. Off in the background, an older Chinese man's comments made the whole group laugh. Karin looked on from what she thought was a safe distance behind the last in the group, until the older man pulled out his passport and pointed to it, then indicated something having to do with Karin and himself, but she quickly pointed to Marc and said, "Zhanfu" (husband). The group roared with laughter -- no telling what his plans were!

A train worker tried to ruin the atmosphere by tapping Karin on the shoulder and waving his index finger in the direction of the other car, but our newfound friends set him straight and took the opportunity to find out which car we 'lived' in.

We made it back to our bed hours later, but stayed up talking to Zhao, who was due to arrive at his destination at 11:00pm. He told us that Han Chinese, like himself, weren't safe in Xinjiang (sin-jahng) Province, which explained why he hadn't stuck around earlier. He won't go to Kashgar in the far northwest because "Chinese aren't liked there." He explained that the government forces the children of the rich to go to school in Beijing in order to control and assimilate them! We said "Goodnight" to Zhao, ending our day on a much more 'pleasant' note.

At 7:00am sharp, we were blasted into consciousness by music which sounded like someone pulling the tails of a thousand cats. This was followed by an announcement that could only have been meant: "Get your lazy bones up and off those bunks, now." While the rest of the passengers obeyed the orders, we put in our earplugs and dug in deeper until 8:30am. We were on vacation with no deadlines.

The terrain became more arid as we rumbled along, with adobe homes spotting the landscape the entire way. Scrub-brushes dotted the sand dunes, while herds of sheep kept shepherds company. The track mostly followed the Yellow River where its muddy-brown waters had carved a path through the undulating, golden beach sands of the Tengger Desert.

The Yellow River is the second-longest river in China and the birthplace of Chinese civilization. It originates in the mountains of Qinghai and meanders 5460km (3400 miles) through the north of China into the ocean east of Beijing. The river takes its name from the color of the unusually large amount of silt it carries. This silt continually raises the river's level making it necessary to contain it with dikes, some as high as high as 15m (50 ft). The river has always been regarded as 'China's sorrow' due to its tendency to flood.

Scattered throughout the desert were dark, contrasting patches of green agricultural plots. There were grapevines, cemeteries, and even something that looked like a castle in a water park. As evening fell, we crossed into rockier terrain, where some barren, desolate, brown hills spread out below for many kilometers. They formed a dense pattern of low peaks, looking like the face of a meat tenderizing hammer. Some of the hills had cave-homes dug into them. In stark contrast to the surrounding dry landscape, there were a few fields of planted grains and vegetables. These oases were caressed by the wind -- some had 10m-diameter (31 ft) sinkholes in the middle of them.

As the sun set, Marc finished Rudyard Kipling's Kim. This was fascinating introduction to Western China, Pakistan, and India, as well as The Great Game. Following the Yellow River, the train passed a string of lights from a chairlift tracing the spine of a mountain. We rolled to a stop in a modern city of three million, on the edge of the frontier.

Lanzhou

From the moment we got off the train we knew we liked this place, even with its construction noise and dust. We were surprised at how comfortable it felt outside. The temperature was pleasant and it had a nice atmosphere.

We had no problem getting a bus to the hotel with the help of locals, who happily got us on the right one. The conductor made sure we got off at our hotel, and a passenger who got off the bus with us, escorted us all the way to the front desk.

The first person we met in Lanzhou (lahn-joe) was Kersti, a friendly woman from Hamburg, Germany. She was fluent in Chinese and had been studying Asian Marketing in Lanchang. She helped us get checked into a nice double and told us about life in China until bedtime arrived.

The next morning at the travel office, we met two Dutch women who had taken the Trans-Siberian railway six weeks earlier. They had travelled for three months seeing most of China. Jeanette, a painter in Castricum, whose father is a "stiff-necked (meaning proud) Frieslander", was raised in the south of Holland. She is a 67-year-young grandmother, who has been a backpacker 'forever'. She lugs at least 21kg (48 lbs) on her back, has travelled across the Sahara Desert, and is very happy and lively, as well as being in great shape.

Dorine, her travel companion from Amsterdam, had travelled through India, where she learned English. They met on a tour-package in Algeria and had travelled together since. The girl from the travel service escorted all four of us on a search for vitamin-C and decongestants at the pharmacy.

Afterwards, we shared travel stories over lunch and the ladies brushed up on their Dutch language skills. Jeanette even gave us a pile of drop (Karin's favorite salty, Dutch licorice), and some oral rehydration salts (ORS) which we'd been unable to find in China. Dorine had lost her flashlight on a tour bus in Xiahe, so we promised to look for it while there, and deliver it to her in Holland if we found it.

Saying "Tot ziens" as they left to catch a train, we knew that we'd run into them again somewhere along the way. We hopped on a bus and headed to the center of town to find the Public Security Bureau (PSB). We had no problem getting our second one-month visa extension from the nice staff for RMB 50 ($6) each, double what we had paid in Kunming.

We walked through the alleys, past some amazing peaches, then strolled along the main road full of women's clothing stores. Finally finding a European-Asian Department Store, we replenished our worn-out wardrobe. On our way back 'home', we tried the smooth and delicious yogurt, recommended to us by a traveller we had met a few months earlier in Laos.

Lanzhou brought back memories of Indonesia and Malaysia. There are a few mosques, and we saw women with scarf-covered heads and men with white Haji caps, but we doubt many have been to Mecca.

Our favorite hangout was without doubt the night market down the street, where the aromas, sights, and sounds would entertain us for hours. We soon discovered that the ruo-jian-biao, a thick flat bread split open and filled with fried mutton, onions, and bell peppers, was as tasty as it smelled and looked. We could have eaten five more, but we had spotted other delights earlier.

We continued walking through the market, scoping out the other stalls until we found a grill covered in simmering clay pots. They were filled with glass noodles, tofu, seaweed-like leafy vegetables, and squash slivers, topped with breaded pork balls. They took our order, dumped the contents of a bowl up-side-down into another bowl, served it with a flat Muslim bread, and charged us a mere RMB 4.5 ($.50). We knew we had no choice but to sit down and enjoy the ambience while devouring our savory and filling meal. Hoped to find more where we were going.

Later, we sucked down two liters of water, probably due to the combination of Mono Sodium Glutamate (MSG) in the food and the very dry desert climate at 1600m (4900 ft). MSG, a naturally-occurring chemical that looks like salt, is called a 'flavor enhancer' since it makes your tastebuds come alive. It is known as: MSG and Accent in the States, Vetsin and Glutamaat in the Netherlands, Tasting Powder in Pakistan, and Aji-No-Moto in Japan, It's called Weijing in China, where they have a saying, "Only a bad cook uses weijing." It's not easy to remember to say, "Bu yao weijing" at every meal, and it rarely works.

In some countries, MSG is banned since many people are sensitive to it, and have had bad reactions. We can handle it pretty well, probably because we had built up a tolerance, but sometimes the cook got carried away, and we would go home wondering why we were so thirsty. Thirty minutes later, and a liter of water each, we knew the answer.

Some nights we couldn't sleep too well, our heads thumping from the increased heart rate. Our worst reaction kept us up until 3:00am, and then it was a restless night of frantic dreams. By the end of our stay, we were eating only two meals per day, and limiting the number of dishes we would order. There is no mystery now why many Chinese menus in the States say, "We do not use MSG." We were surprised to find out how much of it is used in the States to marinate fried-foods, and also how prevalent it is on the ingredient lists on spice jars.

Back at the hotel we again ran into Kersti. Her husband Trykver, and brother-in-law Ingjalt, had just arrived from Germany and Beijing to join her for a journey along the Silk Road. We stood in the hallway and listened to their experiences, which ranged from the flag-raising ceremony at a Japanese-owned Asia Supermarket in Beijing complete with choreographed motorcycle show, to their Lijiang visit shortly after the earthquake. They described how people wasted no time rebuilding their homes, first pulverizing the fallen adobe, then re-mixing it with water.

We exchanged stories about our great day and soon moved onto a higher level of exchange. Kersti's eyes lit up when she heard about Karin's latest acquisition, the drop liquorice. She started dancing and offering anything from her huge German care-package that just arrived. It was our turn to get excited when she donated a chunk of Gouda cheese for a few pieces of 'drop'.

Feeling guilty, Marc surrendered three books, including Vonnegut's Slaughterhouse Five, to 'even' the trade. It was one of the few things we had, but Vonnegut would love the irony since the book is about the bombing of Dresden. Things only got worse when Trykver retaliated by giving us half a German salami. Kersti wasted no time starting in on the drop, as we carefully tasted tiny slivers of our gourmet delicacies in a futile attempt to prolong their lifetime.

The next day, Karin wandered through the market (a fun place to interact with the Chinese) buying fruits and vegetables, always plentiful and fresh in China. Lunch was delicious cheese, sausage, and tomato sandwiches, followed by juicy peaches for dessert.

We bought the scam travel insurance for the buses so we could get tickets for the next leg of our trip. This bus station had the most convenient design we've ever seen. You walk in the front, buy tickets at the windows along the right side, then walk through the building to a loading dock for bus roofs. "Don't fall over the edge." You walk straight out on top of the bus and secure your bags, then take the stairs down to get into the bus.

A group of Westerners, who didn't realize we would be picking up more passengers along the way, had used the entire back row of seats as storage, opting not to put their bags on top of the bus. The crew got mad when they wouldn't move the bags, and went into the station, returning with a fierce little woman to yell at them. Pretty soon they came to understand that the bus wasn't moving until the bags were either on top of the bus or under the seats. A third option of paying full fare for each occupied seat soon materialized, and we were on our way when the bag owners decided to splurge.

In front of us were three rowdy guys wearing beige photographer's jackets. Marc quickly got acquainted with them on the eight-hour bus ride. The one in the middle was a blonde American wearing a Turkish cap, the other two were bearded Turks. Marc started off by telling them that they looked like an offshore speedboat racing team, but without helmets.

Arif Asçi, the wild man in the group, was wearing a Turkish hat that looked like a small, beige, flat-bottomed burlap bag. He rolled his hat down over his eyes when he napped. He was carrying two extremely expensive Leica cameras, one small and one huge. He explained that they were traveling by camel. Marc laughed and said, "Oh, that's what I smell!" He insisted that they had left their camels at their hotel on the outskirts of Lanzhou, so Marc asked, "At the caravanserai?" Surprised, Arif turned to his friends exclaiming, "He doesn't believe me!" then reached into his bag and pulled out a very professional, glossy 8x11 (A4) brochure for us.

Their brochure, The Silk Road by Camel Caravan from Xian to Istanbul, showed their sponsors were ANA, Leica, Fuji, etc. It displayed their photos, their plans, pictures of the Silk Road, and a map tracing the eighteen-month journey they had started six weeks earlier. A team of four, they were the first to make the journey down the Silk Road in three hundred years.

The Turkish president had written letters on sheepskin to all the presidents of the countries through which they were trekking. Explaining their purpose when they presented their letters to Jiang Zemin, he gave them letters expressing his appreciation, especially with helping to boost China's tourist industry. He also guaranteed that they would help. They still had to negotiate the price of permits down to US$17,000 from US$50,000, which included the CITS guy who tried to force them into expensive tours.

Arif Asçi, an art historian and spokesman, is an artist who had become a photographer ten years earlier. He had travelled extensively through China and the Central Asian countries. When the Russian Republics opened up, he realized that with his similar language he could communicate with most people. After reading hundreds of books to prepare, he spent a year faxing sponsors, and they all agreed to support his dream of retracing the famous route. He planned on doing a book of photos, magazine article photojournalism, and a video documentary in English, Turkish, and German.

Paxton Winters, an experienced backpacker, and filmmaker who spoke some Turkish, was doing the video documentary, as well as photography and sound. He also had a laptop for uploading email and stories to the Internet. Within a month, he expected to have a satellite phone. We gave him many tips since he was new to the Internet.

Paxton sat in the back of the bus once trying to type, but found it too hard to find the keys between bounces. He was not pleased with the Turks' fear of computers and their refusal to recognize the promotional possibilities. The rest of the team, Necat Nazaroglu and Murat Özbey, were reporters in Turkey as well as being photographers for the caravan. Murat, the quietest one in the group, sat behind us with his German girlfriend.

Trekking 5-20km per day and resting one week per month, they were going to take the low route through the Taklimakan Desert. Next they planned to cross into Kyrgyzia, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, and Turkmenistan. After Iran, they would go into Turkey and cross the Anatolian steppes.

Arif explained that they needed to get to sand, then on to Kashgar, where they planned to replace the ten camels they bought in Inner Mongolia. The camels were in poor health, one dying from the walk to Xian and another being put to sleep since its soft and tender foot swelled from the asphalt. Their budget was limited, and camels cost US$100-US$300 each. He told us about the coal truck drivers who communicate "hello" by honking their air horns, scaring the camels and causing them to buck, dumping their loads and costing the team an hour to reload. When Arif caught up with one of the trucks the next day, he knifed a tire to prevent him from doing it again.

We stopped at a Muslim restaurant in Linxia (links-see-ah) for mutton and noodle soup with bread. Then we rattled another three and a half hours on the bus through 4000m-high (12,500 ft) mountains, some were green, some desolate brown. We started seeing fields of yellow flowers, Tibetan stupas, and yaks on the second half of the ride.

A little further on we noticed some interesting roadside billboards. They each had a large photo of a person with some information, and a checkbox in the upper left corner, some of which had been checked off. Two women teaching English explained that these were "Most Wanted" photos with a listing of crimes. The check in the box meant that they had been executed. China had executed 1000 people in the last two months, many for petty crimes. This was part of a massive crackdown on crime known as the "Strike Hard" campaign. Another man explained that the annual numbers could be much higher than the six thousand that had been reported. Executions are public events attended by 1.75 million people. Sometimes they are held in stadiums, while cheering crowds applaud the executions.

In March 1998, Utne Reader reprinted a Sciences article by David Rothman called "Body Shop". He went to investigate China's booming organ-transplant business and ran into a chilling wall of silence. "Nobody would admit, let alone discuss, what I knew from many other sources to be true: that executed prisoners are the primary source of China's organs, and that citizens from Hong Kong, Taiwan, Singapore, and other Pacific Rim nations travel regularly to China to obtain them." After human rights groups uncovered Chinese government directives that clearly showed that they were removing organs from executed prisoners, the government admitted it, but said it was "rare".

On February 25, 1998, Associated Press reported that the FBI conducted a sting operation in Manhattan. Two Chinese men were charged with conspiracy in a scheme to ship body parts of executed Chinese prisoners to the United States and to arrange for Americans to travel to China for the transplant of kidneys, corneas, livers, and lungs. Then, in the March 9, 1998 issue, Time followed up with an article entitled "Body Parts For Sale." The controversy arises, as it always does with harvesting organs, over how the donations are solicited and under what circumstances they can be used. The problem is that in China, the condemned donate whether they want to or not and the government keeps the money.

Xiahe

Arriving at Xiahe (sheAH-her, or seeAH-her)

in the mountains of Gansu Province, we encountered a light sprinkle of rain and

ten dirty kids and men all saying, "Labrang Hotel." We escaped by

rushing off the bus and taking shelter in the station while they circled the

rest of the travellers who were busily rounding up their luggage.

ten dirty kids and men all saying, "Labrang Hotel." We escaped by

rushing off the bus and taking shelter in the station while they circled the

rest of the travellers who were busily rounding up their luggage.

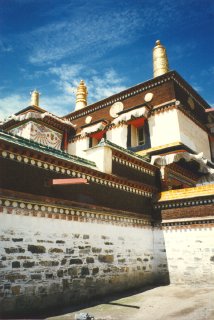

Having prior knowledge of the highly-recommended Tara Guesthouse, we waited for the crowd to disperse, loaded up, and went for a ten-minute walk up 'the' road. We passed hundreds of monks in crimson-burgundy robes, as there are more than 2000 monks studying here. Tibetans are noticeably different from the Hans, and have ruby-colored cheeks like the Mongolians. While still not used to foreigners, they smiled a lot.

We got a triple room for the price of a double and paid for three nights. This was the minimum number of days we knew we would need for a village this nice. Tsering, the hospitable owner from Darjeeling (India), had travelled to San Francisco and spent the previous three years working in downtown New York City. She told us she worked in a Polish/Ukrainian restaurant on the corner of 2nd Avenue and 9th Street. She returned to Xiahe three months prior, after hearing that her husband was sick.

At 2920m (9050 ft) elevation, the skies were a beautiful deep shade of blue. The sun was intense during the day, yet it didn't take long for the mercury to start dropping once the bright, full moon made its appearance on this clear evening. Going next door, we had a hot dinner of sweet-n-sour eggplant, vegetable and noodle soup, and pungent Tibetan yak-butter tea. Finishing this, we wasted no time in the freezing temperatures, rushing home to dive into our cozy sleeping bags.

Persuading ourselves to leave the cuddly warmth of the sleeping bags the next morning wasn't easy. However, this town had much to offer and we knew we'd have to come out eventually. We later learned that our room was the coldest in the hotel, so we convinced Tsering to move us to another room on the sunny side of the building.

After a splash with ice-water from the barrel on the terrace, we ventured down to the street corner for a loaf of heavy Tibetan bread, then back to the hotel. We stopped by the kitchen for fresh yak yogurt on our way up to the lounge, affectionately known as the 'glasshouse', and also a good place to meet travellers. This was a warm sunny room with large glass windows on three walls giving a panoramic view of the valley. From this vantage point, Xiahe looked surprisingly similar to the pictures of Lhasa in Tibet.

After breakfast, we went for a stroll through the lamasery, accidentally straying into monks' residences in a 80x80m (250 sg-ft) compound. Monks in their teens and twenties were playing ping-pong (table tennis) on a concrete table and invited Marc to play -- they were easy on him! Funny watching them run in Tibetan shoes while wrapped in yards of burgundy wool robes. Karin pulled out the camera, took some photos, and was instantly surrounded by five curious monks. They nearly drained a pair of expensive and rare batteries playing with the zoom feature, until she finally buried the camera in the bag.

It was interesting to see how happy, friendly, and unafraid of women the monks were. Thai monks tended to jump out of their skin whenever they come face-to-face with a woman. When Karin broke out the language book, one of them pointed at her watch, then at the "How much do I owe you?" phrase in the book. Karin did what many people do to us, she pretended not to understand. After a second round of ping-pong, we wandered around the compound some more. We were soon noticed by someone at the front gate and shown the way out, meaning we got kicked out.

Locating the official entrance to the monastary, we blew past the unmanned ticket office -- it was lunch time. We joined a tour group of country-Chinese led by a monk. There were old farmers in blue or green polyester Mao suits, with some of the women having tiny feet from being bound. Following them into a temple, there were colorful and scary frescos and the usual array of Buddha's. The fragrant smell of yak butter and the sight of monks everywhere gave us the feeling that the place was alive, unlike the one in Beijing. Not being able to follow what the monk was saying, we abandoned the tour.

Meandering back towards town, we soon spotted the Turks having lunch. We joined them for yogurt, steamed rice, and a plate of beef, onions and tomatoes. Murat cooked, after Arif refused to accept the 'beef fat' and onions the waiter brought out. When the waiter brought the bill, Arif scribbled all over it, determining the new price. The owner reluctantly accepted it after Arif said something in Turkish and the owner's attempt to discuss the bill only found Arif's hand pushing it back. The rest of the group is in for a helluva eighteen months.

We went to Mansu's restaurant to get Dorine's flashlight from the owner. He knew where it was, but needed a day to retrieve it, basically holding it hostage while trying to get us to take one of his tours. We weren't biting, so he invited us to the back of the restaurant and into the kitchen, trying to make us uncomfortable and pressure us into accepting the tour. We left quickly, letting him know that we would see him soon.

At our hotel we met Dawn, a funny and talkative New Yorker. She had been teaching English in Shandong and explained that, "There's nothing worse than a classroom full of children who think they're the center of attention, all spoiled rotten!" The greedy guy who recruited her refused to give her the contract that he promised, and cut her pay after she arrived in China (not an uncommon story), so she went on strike and wrote letters to her students' parents explaining why she was refusing to work. Things finally settled down and he gave in. Now she likes teaching there enough to want to study Chinese Literature or World Studies when she returns to the States.

We went to dinner with Dawn. The baked vegetable momos (Tibetan steamed buns) were excellent, the eggplant was okay. The chicken, on the other hand, was overcooked and tough and we had to send it back. Still, the owner put up an argument when we paid only half the cost of the chicken. Dawn held her own and we finally had to walk out, but the owner blocked the exit. After five minutes of calm negotiating, Marc raised his voice and the owner finally gave up.

We went back to the hotel lounge in search of a warm place to talk until bedtime. It was a very popular hangout, so we were soon in a deep discussion of routes and strategies with the other guests who were also west bound. Hamutal, from Israel, was making a detour in her trip so she could see the Turkish team's camels in Lanzhou. Dan and Emma from England were on their way to Dunhuang. Tony and Mindy from Australia were on the same schedule as ours heading for Pakistan.

The next day, we joined the 'lounge crew' for an official tour of the Labrang Lamasery (17th century), this time with a tour leader who spoke a few words of English. The interiors of the temples had more large and impressive seated Buddha's, beautiful wall frescoes, and scary wall paintings better seen in books than described here. One Buddha pose represented: "It's OK!" There were very detailed one-square-meter sand paintings under glass, 2000-year-old tusks from India, and ancient Tibetan chain mail used in battle. The main hall that seats 4000 was immensely colorful and the artisans much more skilled. All buildings were slightly warmer than a meat locker, some housing exquisitely-carved yak-butter sculptures.

When the tour ended at 12:30pm, we heard the sound of music. Tracking it down to a grassy courtyard with trees, we found a monk blowing a 3m-long (9 ft) horn which was supported on the ground. Two older monks played meter-long high-pitch horns. We sat in front for the low bass vibes, while the trio continued playing, seemingly oblivious to our presence.

Trying to get into another temple, we were quickly chased out. We roamed through the east end of the lamasery, then went south along the base of the mountain, turning the prayer wheels. These signify that the Wheel of Life (symbolizing the levels of rebirth) keeps turning, and helps worshippers concentrate on their meditation. We exited back onto the main road. Back at the Tibetan restaurant across from our hotel, we sat under a tarp in the back courtyard, eating mutton-filled momos and Tibetan tea made from yak-buttermilk.

Later, in our search for more momos at dinnertime, we ran into the Turkish guys, who recommended the same place we ate lunch at. Some teenage Tibetan girls, deeply tanned from exposure to the intense sunlight in the mountains, joined us for a bit when Arif teased them. The wildest-looking one in the bunch wanted to see the hair on the men's arms, then jumped and screeched when she saw Arif's. The group ran away screaming when they saw Paxton's legs. They returned and the leader wanted to see all of our chests after having seen Arif's. When he asked to see hers first, she shrieked, "Meiyou!" which this time meant "No way!" They ran away, not to return, when Paxton jokingly threatened to cut the leader's long braids with a large knife that Arif carries on his side.

Up at 5:45am, we speed-packed, bought a loaf of Tibetan bread, then caught a trishaw for a five-minute downhill roll to the bus station. No large buses, so we bargained with a tout who insisted his minibus was going to Lanzhou, although the characters for Linxia were on a small sign in the window, and everyone getting on board was going to Linxia. His asking price was four times what we'd paid to get here, but we got him down to half that rate when we showed him our original Lanzhou-Xiahe tickets with the fare. He decided to collect as soon as the bus got rolling, so we changed our destination to Linxia (the halfway point) and paid him what everyone else was paying -- he was not happy, but we were.

At the bus station in Linxia, a swarm of touts descended upon us, asking way too much. We went inside and bought tickets at the counter, and a tout escorted us to a minibus. Minibuses were lined up in the alley outside, but ours was only half-full, so the driver was in no hurry to leave. Suddenly there was a mad rush of buses reversing downhill into the alley, almost colliding into each other -- police officers in white uniforms were walking in our direction.

Our driver wasn't quick enough and ended up having to surrender some papers and stand on the sidewalk with a sheepish, embarrassed smile. He was surrounded by a crowd of curious gawkers, while the policeman shared some words of wisdom. Next thing we know, the driver is back behind the wheel. Doing a U-turn, he drove us out the back of the alley. He parked the bus half a mile away on a bridge and waited while the other tout ironed out the wrinkles. Once he recovered his papers, the bus was almost full and we were ready to roll.

Lanzhou

Once again in one of our favorite cities, we wasted no time resorting to old habits. We frequented the markets night and day. We ran into Hamutal and joined her to meet the Turks for dinner at the night market. There was no trouble spotting them shopping for watermelons. Settling at a nearby stall with the right 'menu', we got a table for eight. Murat ran off and came back with beer and fried rice, while the waitresses served beef and noodle soup. Fried mushrooms, cauliflower, skewered mutton and bread rounded out the meal. It was a feast for the palate.

Dessert started when Arif broke out the watermelon and applied his huge knife. He split it in half lengthwise, then quartered each half. Cutting vertical slits along each wedge, he ran the knife along the rind, leaving juicy triangles. The staff finally threw us out after they had cleaned all the other tables. We made it back to the hotel in plenty of time for the 11:00pm curfew.

We had been told that the woman at the train station window for foreigners was rude and would try to sell us expensive tickets. Surprisingly, she smiled for Marc and gave him the correct tickets. No two situations seemed alike, but this one couldn't have been any easier. Wish she spoke English so we could have thanked her properly, and heard her side of the story about foreigners.

Hotel maids all over China must go through similar invasion training. They invariably have the same technique of unlocking the door, then knocking as they enter the room. Some don't even bother knocking. We resorted to more severe tactics, having given up politely asking them to knock and wait for us to respond. The first 'close encounter' with our exposed anatomy brought immediate results. Quickly salvaging their composure, they learned to knock before barging in! Customer service has a long, hard road ahead of it.

In the market, we ran into Yafit and Eron, an Israeli couple we met in Beijing. They had gone to Ürümqi, and were heading for Xiahe, but were afraid of Kashgar due to rumors about fundamental Muslims. Their train ran out of water, so they had the bright idea of boiling some with their gas stove. They saw no problem with this, but a Chinese man got very upset, so they shut it down and put it away. Cops were there fast, and one confiscated it without giving them a receipt. The cops refused to give it back, as promised, when they got in town. They were in Lanzhou to see his boss, and hoped to get it back. They were lucky not to have been fixed and deported!

Our last day in town, we took a bouncy miandi-ride (me-yen-dee, the bright-yellow microbus taxis that look like a loaf of bread, just shorter) out to the truck-stop hotel where the Turkish team had three rooms and parking space for the camels (a modern caravanserai). Going out back to see the ten camels, we took some pictures. Murat was like a kid, running around with lots of energy and playing with the meter-high (three feet) kangal dogs. At nine months, these dogs were already huge.

We all piled into a miandi to go to the university. They had been invited for lunch by students they'd met at the market the night before. The ride seemed to last forever, and by the time we got there it was time for us to head back and catch our train. The caravan completed the trip in November 1997, and in 1998, they published their book, "The Last Caravan On The Silk Road." For more information about the Silk Road, visit: Silk Road Foundation.

Back at the hotel, the group we'd met in Xiahe was in a state of panic. The Chinese travel agency, which had been so friendly and helpful to us, had bad news about their train tickets. Dan and Emma were having problems with their tickets and would not be in the same car with Tony and Mindy. It's at times like these that we were glad we had the independent ticketing routine down.

Having some time to spare, Karin went to the market to stock up on food for the road, while Marc stayed with the group. When it was time to load-up and relocate to the train station, the travel agent volunteered to help us get a miandi. There was no way to fit all six of us with our bags into one miandi, so he came up with the bright idea of putting all the bags in a separate miandi. None of us was quite ready to wave goodbye forever to our bags as they rode off in a speeding miandi, so we split up and piled into two miandis for the race to the train station.

Once there, Dan drew attention to himself by stepping on and over a row of back-to-back seats, enraging an old man in charge of order in the enormous waiting room packed with nearly three hundred people. It was too late to take it out on Dan, who was now in the other aisle, so the man ran up to Mindy (137cm or 4'6" tall), pushed her, and told her to go around. Marc ran between them, and being 186cm (6'1") in his boots, with a beard, the man kept a respectable distance and pretended not to notice when Marc started pointing at him and the other old man who started pushing Dan. Things calmed down, but Dan was not allowed to sit while we waited twenty minutes for the train to arrive.

We were on the train when it pulled out at 5:00pm heading farther west, but each couple was in a different car. Marc got talking to Ming, an industrial pump salesman who spoke some English. He took Marc to the dining car to buy water, and when it didn't have any, he went seven more cars and bought it for Marc. We are starting to think that the best way to meet Chinese people is on trains, where they can relax and be themselves.

At one point, the guy on the bunk above us, who works for the railroad, started smoking. Marc asked him to stop and pointed to the 'No Smoking' sign. He was reluctant, but left. Later, when Marc ran off two more smokers, the old people in our car showed their appreciation by nodding and smiling. There were no hard feelings later, as harmony is the most important thing here.

It got cool suddenly as the train started climbing into beautiful green grasslands. Around 8:00pm the gang showed up on their way to the dining car to celebrate Emma's birthday. We secured our bags and followed with a cup of tea. Sharing the famous birthday song, we offered some cake to two Chinese students who joined us to practice their language skills. One of them, who wants to teach English to the locals, invited us to his village to see the wheat being harvested. At 9:00pm a waiter came over to us, and tried to charge what would amount to his day's wage for the table. He tried to justify this saying it was "cocktail hour." We stalled him for awhile then called it a day.

The CITS agent in Lanzhou told Emma and Dan that the ticket problem had been corrected. They were laughing about it on the train because they thought he had made a RMB 300 (US$36) mistake. Now they were upset as they found out they were only ticketed halfway to their destination. At that point, they would have to move from the sleeper compartment and join the herd in hard seats at 1:00am.

Around 11:00pm, Emma woke us, saying she hadn't seen Dan in hours. We ignored her, since we were tired, especially of them. He could speak Chinese, and had met some people to talk to. At 1:00am, beds in the sleeper compartment were available, so they bought them, but not without a steep "service fee" for the conductor.

After a comfortable nine hours of sleep (since the speaker was broken), we woke at 8:00am to a dismal view of rocky sands on a flat, barren, hot plain between brown snow-capped mountains. The train rolled by the Jiayuguan (jah-you-gwahn) Fort at the end of the Great Wall, reaffirming that this was farewell to the Han Chinese. From there the terrain got flatter and sparsely fertile. The sand was black on top, as if the earth had been scorched by a fire. The dark ground stretched outward until it transformed into pink rocky mountains in the distance.

As it got hotter, Karin took a nap. Marc talked with a young Chinese engineer-in-training who used to work with Americans in Lanzhou. He now works with the Japanese on building projects in Dunhuang, an oasis in the desert. The caves are a UN World Cultural Heritage Site, much nicer than Datong's. They don't let you see many of the caves, because they have drawings that are considered pornographic by the Chinese. It is also a popular hangout for backpackers, like Dali and Yangshuo, so we bypassed it.

Visiting the Aussies, we confirmed plans to rendezvous in Ürümqi and Pakistan. Hamutal, Dan, and Emma had gotten off the train in Dunhuang. They planned to be in Dharamsala at the same time we would be there, after visiting Tibet, Nepal, and India. This is one of the typical looping routes that many travellers take in this region. The desert looked like an open-pit mine, with land just cleared for construction.

Later on, it turned beige with more sand and less rocks or colors. The magic number seems to be thirty-six hours for our train rides, and this one covered 1800km (1100 miles) of desolate landscapes. At 6:00am the train attendant hustled us out of bed, giving us just enough time to clean up and get our bags ready. The sunrise gave the town outside a deceptively warm glow.

We hopped off at the 'Turfan station' in Daheyan, a bleak little place whose claim to fame can only be its proximity to Turfan. Buses were waiting, but strangely, nobody tried to get our attention. Everyone else seemed to have the same idea, as they walked out the small gate, so we followed them.

Walking a few blocks to the bus station, we found a minibus that was already full, so we parked ourselves on the terrace out front. A tout in his forties came over and offered us twice the normal fare. We checked inside at the window and they quoted us the same fare, and told us we would have to buy our ticket from the bus driver.

Karin left Marc in charge of the bags and touts, and went in search of food, returning with some oily mantou bread and tasty Muslim bread. We asked the next driver who came over, "How much?" and he also failed the test, so we said, "No, thank you," and the bus left half-full without bargaining. Word got around, and a third came over and asked if we were students. We showed him our 'teacher cards', and he answered with the right fare.

Loaded up with good seats, we were rolling by 7:30am on July 6, 1996. Our path followed along a rocky, dry riverbed in between distant mountain ranges. This is a vast glacier melt-zone, and in some places the road had washed-away, making for a bumpy ride. An hour later, we arrived to the scorching 47°C (116°F) heat of the Turfan Desert Basin, the second lowest depression in the world and one of the hottest places on earth. "Welcome to Hell!" said the sign in Chinese.

Although we settled down in August, we had to return to Curaçao for a few months. We have acclimated to life back in the States pretty well, and it has been nice hearing from everyone. If you would like to know when new dispatches are available, send us a note and we will add you to the mailing list.